Welcome to the last installment of our Africa supply chain series. Part 1 talked about geography, demographics, and the economy, and Part 2 was about challenges and opportunities. Today, we’re tackling the complex landscape of African pharmaceutical regulations.

Specifically, we’re looking at the African Medicines Agency (AMA), envisioned as a single regulatory body that would cover all 54 countries on the continent. It’s a big topic, but we’ll break it down into easy-to-understand terms. Let’s get started.

African pharmaceutical regulations: defining the key players and terminology

To understand African pharmaceutical regulations, you have to know the key players and be familiar with some core vocabulary. Today, we’re talking in broad terms to establish some baseline knowledge; if you want to know more about any of the entries below, just click on the linked text.

African Medicines Agency (AMA): According to its business plan, the AMA’s vision is “a healthy African population with access to quality, safe, and efficacious medical products and technologies.” It was established in January 2015 and officially began in November 2021 after 15 countries signed and ratified the AMA Treaty and deposited their instruments of ratification with the African Union Commission (see below). The AMA does not yet have a website; visit the African Union website for more information.

African Medicines Regulatory Harmonization (AMRH): Formalized in 2009, the AMRH is an initiative to “provide leadership in creating an enabling regulatory environment for pharmaceutical sector development in Africa.” It is part of the African Union Development Agency (see below) and the Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Plan for Africa (PMPA).

African Union (AU): The AU was launched in 2002, succeeding the Organization of African Unity, which was active from 1963 to 1999. It comprises five regions and has 55 members: Central Africa (9 states), Eastern Africa (14 states), Northern Africa (7 states), Southern Africa (10 states), and Western Africa (15 states).

African Union Commission (AUC): The AUC is the AU’s secretariat and runs the day-to-day activities of the Union. It is based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD): AUDA-NEPAD’s mandate is to “coordinate and execute regional and continental projects to promote regional integration towards the accelerated realization of Agenda 2063” and “strengthen capacity of AU member states and regional bodies.” (See Part 1 of our series for more about Agenda 2063 and read the AUDA-NEPAD 2021 Annual Report here.)

National Medicines Regulatory Authorities (NMRAs): Each country’s NMRA is responsible for regulatory functions such as marketing authorization, pharmacovigilance, market surveillance quality control, clinical trials oversight, licensing establishments, and laboratory testing.

Regional Economic Communities (RECs): RECs are regional groupings of African countries formed to facilitate regional economic integration and the wider African Economic Community. The AU recognizes eight RECs:

- Arab Maghreb Union (UMA)

- Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA)

- Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD)

- East African Community (EAC)

- Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS)

- Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

- Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD)

- Southern African Development Community (SADC)

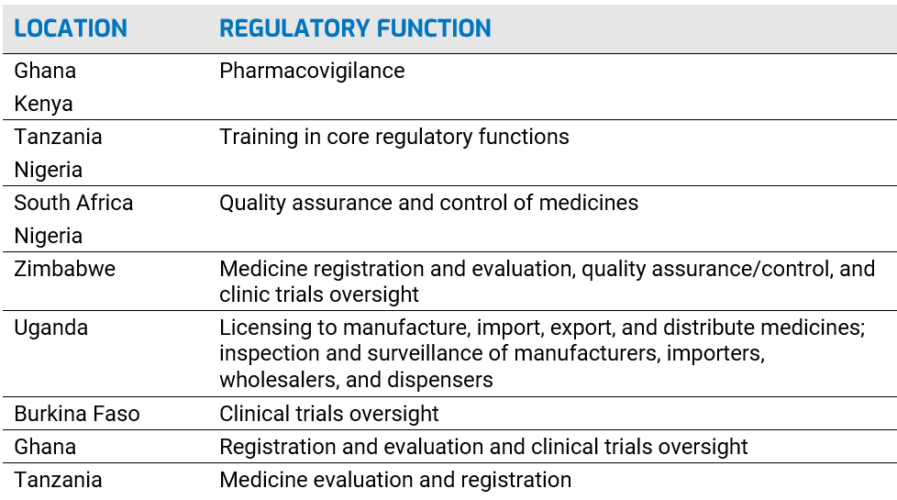

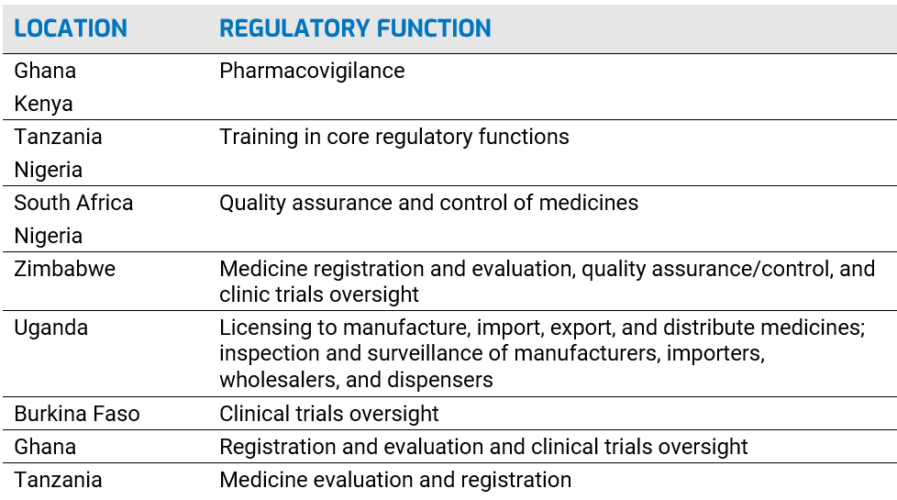

Regional Centers of Regulatory Excellence (RCORE): AUDA-NEPAD, through AMRH, designated 11 RCOREs to work in eight regulatory functions to build regulatory capacity at NMRAs:

African pharmaceutical regulations: current context

With the AMA going into force barely five months ago, and considering the vastness of the African continent and the diversity of its countries, it should be no surprise that the current context for African pharmaceutical regulations is … one of flux.

Authorities (e.g., the AU and AUDA-NEPAD), through the NMRAs and RCORES, as well as through coordination with the RECs, are working through the many challenges of harmonizing regulations. There are a lot of moving parts that need to coalesce under the AMA umbrella. For example:

Different legal and regulatory frameworks. Many countries and RECs have developed or are developing their own regulatory legislation. But right now, it appears they are not obligated to coordinate, standardize, or harmonize their laws. Therefore, regulations can vary from country to country in a REC, and any country’s laws might also diverge from their REC’s requirements. Regulations also vary from REC to REC, such as the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the East African Community (EAC), and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

Furthermore, legal and regulatory frameworks can be unclear and incomplete, and authorities may not make public announcements about their intentions, timelines, and progress. Manufacturers and other supply chain stakeholders may have to submit paperwork to more than one NMRA, which duplicates efforts and wastes resources.

Need for capacity-building. A March 2021 article in the Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice noted that all but one country had an NMRA or “an administrative unit conducting some or all expected NMRA functions,” but only 7 percent had “moderately developed capacity” and more than 90 percent had “minimal to no capacity.” Complicating matters, some NMRAs operate as independent organizations and some operate within their country’s Ministry of Health.

Reliance on imports and the problem of counterfeits. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) estimates that Africa imports about 94 percent of its pharmaceutical and medicinal needs at an annual cost of $16 billion. This is a regulatory and logistical challenge. It also means there are plenty of opportunities for illegal activity. We noted in Part 2 that 42 percent of all fake medicines reported to the WHO from 2013 to 2017 came from Africa. The WHO also estimates that one of every 10 medical products in low- and middle-income countries is substandard or fake, while another report says up to 70 percent of pharmaceuticals could be fake in developing regions.

The African Medicines Agency

These disparities, capacity needs, and logistical challenges were among the reasons why the AU wanted to establish a continental regulatory system. And like other regulatory systems, the AMA is designed to protect people, to ensure that all Africans have access to safe, efficacious, and affordable products that meet international standards.

The AMA is based on the AU Model Law on Medical Products Regulation. In broad terms, its goal is harmonization by achieving the following:

- Registration and marketing of health technologies

- Granting manufacturing and distribution licenses

- Conducting quality and safety inspection of health technologies and manufacturing facilities

- Authorizing clinical trials through an established National Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board

- Overseeing appeals procedures through an established Administrative Appeals Committee

International reaction to the AMA has been mostly positive. The International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations, for example, said that the “AMA has the unique opportunity to become one of the most efficient and modern regulatory systems in the world.”

And just last month before a two-day EU-AU summit, the EU (including the European Commission, the European Medicines Agency, and member states Belgium, France, and Germany) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation announced they would mobilize more than 100 million euros over the next five years to support the AMA and other pharma regulatory initiatives at regional and national levels.

As of March 3, 2022, 30 African countries had backed the AMA: 19 had signed and ratified the AMA Treaty and deposited their instruments of ratification with the African Union Commission; two had signed and ratified but not deposited; and nine had signed but not ratified. Thirteen countries have said they’d want to be home to the AMA headquarters.

Still, 25 countries have not signed the AMA Treaty, including South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, and Ethiopia, four of the most important economies on the continent.

Final thoughts

African pharmaceutical regulations and the AMA are evolving. And like all regulations, there will be stops and starts.

The important takeaway is this: The pharma industry must be prepared for the continent-wide AMA regulations and the AU’s vision of a single authority working with a harmonized set of standards. Though there are holdouts, Egypt, Africa’s third most populous country and an important economic power, has ratified and deposited the treaty. This is a significant event in the efforts to get those countries on board with the AMA.

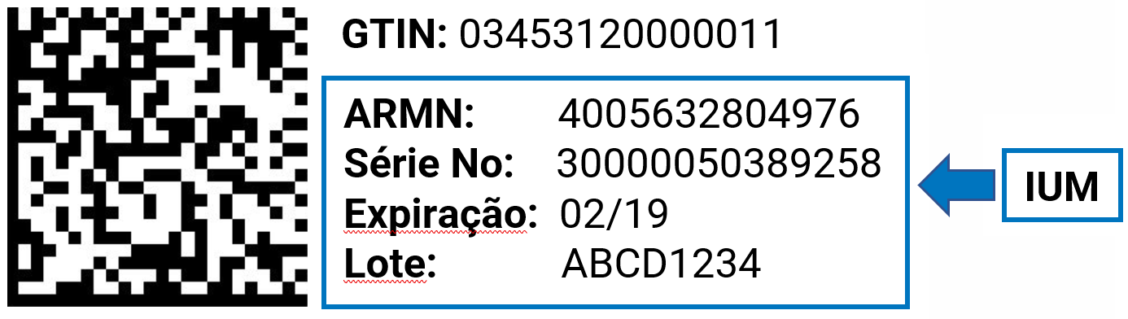

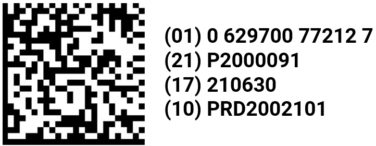

Preparation is the key to compliance and keeping your supply chain running. And we’re experts in making sure you’re prepared for regulations — and every other aspect of supply chain management and optimization — everywhere you do business. Pharmaceutical companies rely on our solutions to comply with strict regulations and to get the most out of their supply chains, from harvesting rich, actionable data in real time to leveraging serialization technology for brand protection and consumer engagement.

Contact us today to speak with one of our experts. In just a few minutes, they can show how our Traceability System will optimize your supply chain today and, importantly, ensure you’re prepared for what’s coming tomorrow.

And if you’re like us and just can’t get enough of regulations and compliance, download our updated “Pharmaceutical Compliance: A Global Overview” white paper. We’ve added more than 25 countries, including REC member states, expanded our “rfxcel Compliance Resources” section, and a lot more. Get it today!

Last but not least, take a look at our other news from the Africa and Middle East region: